I must've been about five. This was small-town Kentucky, 1958, and my dad was letting me tag along to Saturday breakfast. He'd meet up with his pals and they'd shoot the breeze over sausage, hash browns, country ham, fried pies, grits and gravy. It was all bonhomie and that great lard-fried smell behind those plate glass windows.

The grownup talk mostly went over my head. I did pick up that bless her heart wasn't exactly good. There was also a mystery language from back in the kitchen. Flop two, frog sticks, Battle Creek in a bowl. When pancakes went out on the short-order window: Tire patches up! There was Army slang too because my dad's cronies were vets. WWII, Korea. The corner booth was the DMZ.

Sam's Truck Stop had the jukebox, a wonder of plastic marble and glowing lights. No wallboxes in Sam's. You walked over to the wizard to put your coin in and choose your song. That was an extravagance we couldn't afford, but I loved just watching the magic of the mechanical arm and looking at all the passion of the music menu. A letter and a number away were "Tears On My Pillow," "It's Now or Never," "Devil or Angel." And wherever these singers went they had a party in tow: and the Hurricanes, and the Imperials, and the Midnighters.

I deduced from my parents' reluctance to spare a coin for any jukebox that only rich or reckless people threw money around on things like this, so it was thrilling to imagine the hell-bound lives of the perfumed women and occasional pompadoured daddy-o who came up and chunked quarters in. Sam's is where I first heard Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Three.

Hamilton's Drugstore was my favorite breakfast spot because of the comics rack, the soda-fountain, and the fortune machine ("your weight and fortune"). There was even an album bin. I remember trotting over to my dad with a Ricky Nelson. Could we get it? There was some discussion at the table. Their taste ran to Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw. This was that dangerous rock and roll, however scrubbed. The pipe-smoking professor allowed that Nelson wasn't as bad as the others. At least it wasn't that Elvis no-talent. I could see my dad wanted to get it for me. He took me aside. It was just too expensive, he said. Later I discovered 45s across the street at the Ben Franklin. Fifty cents. When I was old enough for allowance I'd save up and that's where I'd go. "Big Bad John" by Jimmy Dean was the first one I ever bought. Later it was anything with a Stax label.

I learned to read in Hamilton's. Garth Elementary too but my memory of getting it is wedded to the magazine corner of the drugstore. Back where I devoured comic books by the hundreds. One day the words in the talk bubbles of Batman and the rest stopped just being in the way. That comes back to me in the clearest memory wave. The letters started communicating and I tore through the whole DC and Atlas pantheons, camped back there on the lowest shelf of the rack.

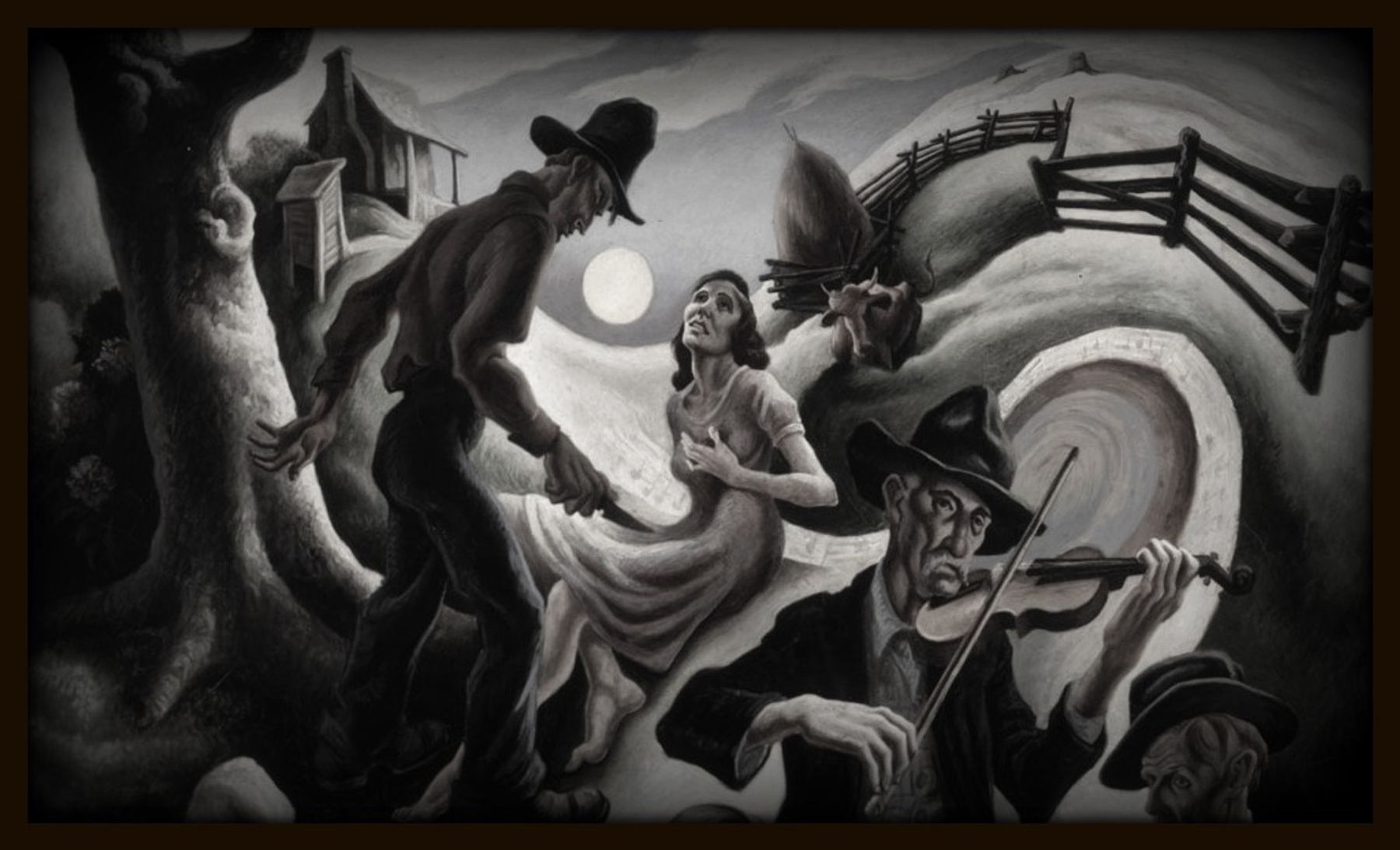

Another thing about Hamilton's is that Uncle John would give me a quarter for a milkshake, which set in motion a beautiful rigmarole of scoop spoon, dipper cabinet, syrup pump, and a surgical-looking spindle, all enacted against a backdrop of chrome and mirrors and flanked by a tobacco-harvest mural someone had painted above the booths that lined the wall. The shake came in a foot-tall steel can that could last through two or three Green Lanterns.

Silver-templed Uncle John, my father's business partner and my grandmother's brother. The others had the crewcuts that meant hard work and no nonsense, but Uncle John had Cary Grant hair and a wink that let you know he knew what was what. In later years he would sometimes just disappear. Gone to Florida maybe. He was the only nicknameless one of those diner-booth lions. Such great names: Smack, Beef, Shorty, Little Doc. Handles worthy of Marvel demigods. My dad was Monk.

They were all kind to me, "little Monk," but mostly I inhabited a knee-high invisibility zone, free to wander at will. I became visible once when they caught me pulling a wad of gum off the bottom of the table to chew. Seemed real funny to everybody but as far as I was concerned it just ruined my good thing. I'd been doing it for a year.

I became visible another time after a jag of reading G.I. Combat comics. I appeared at their booth to ask how many Krauts and Japs they'd personally killed. Shorty, I learned later, was a Bataan Death March survivor.

Leukemia, I heard my parents say one day, their faces solemn. Mr. Hamilton was dying. I knew him as the nice man in the white coat who let me read every last comic book in that whole glorious back-corner rack. He only asked me not to wrinkle them so bad. Leukemia. Such a strange word.

They're all gone now and I've got silver temples myself. Buttering grits and baiting the waitress one day, vanished the next. Carpe gritsem.